In 1707, Scotland united with England to form Great Britain. This opened up trade which led to economic prosperity, and British citizens began to accumulate savings. However, due to years of fiscal mismanagement and the financial drain of being at war with multiple nations, the British government was heavily in debt.

To resolve this, the South Sea Company was formed in 1711 by the British government and private interests—primarily John Blunt. The South Sea Company made itself liable for the British government’s £9 million debt. In return, the British government (1) agreed to pay the South Sea Company 6% annual interest on £9 million in perpetuity and (2) granted the South Sea Company a trading monopoly in South America. Although the South American ports were owned by Spain—who Britain had been at war with since 1703—members of the British government were in the process of peace talks.

Previous holders of government debt were obliged by Act of Parliament to swap their debt securities for South Sea Company shares. Insiders who knew of the deal beforehand bought government debt securities for as low as £50, and then eventually swapped the debt for £100 in South Sea Company stock at par value.

Operational Failures

Two years later, the Peace of Utrecht was signed in 1713, and Spain permitted the South Sea Company to supply Spanish colonies with slaves. While this seemed to be a favorable development, the South Sea Company was restricted to only one ship per year to each South American port, and was furthermore required to give 25% of their profits to the King of Spain. But since the South Sea Company was so incompetent (not a single company director had any experience in South American trade), the mortality rates on the company’s slave ships were too high to make any profits, even though they delivered more than 15,000 West African slaves over the next three years.

This was bad for shareholders, because even though the company was receiving 6% in annual interest from the British government, these interest payments were not being distributed to shareholders as a dividend. Therefore, they were relying on the South Sea Company to profit from trading in South America.

Despite the futility of the South Sea Company’s efforts, its stock was injected with a powerful sense of legitimacy when King George made himself the governor of the South Sea Company in 1717. Since the king himself was now “involved” with the South Sea Company, shareholders assumed that the stock was now “too big to fail.” However, the real reason the King made himself the governor of the South Sea company was because he was on bad terms with his son, George II, who was the original governor of the South Sea Company. The reality was that King George had ousted George II from the South Sea Company’s governor position to punish and humiliate him, not necessarily because he endorsed the company.

Peace between Britain and Spain was short-lived. In 1718, war with Spain broke out again, and the South Sea Company’s assets in South America were seized. The company lost £300,000 and all hopes of trading in South America disintegrated.

The Bubble

By now, it was clear to shareholders that the South Sea Company’s business in South America would never work out. To save the stock, John Blunt hatched a diabolical plan in 1719 to dump shares on the public and have them pay the government’s debt (and more). The South Sea Company proposed to take on all of the government’s new debt that had accumulated since 1710—a gargantuan £31 million. Then, for every £100 of government debt, the South Sea Company would issue stock at a higher value.

John Blunt all but bribed government officials to pass this plan, known as the South Sea Act. He did so by issuing government officials South Sea Company shares that they didn’t have to pay for until they sold the stock.

The plan was approved. The government received a cash payment from the South Sea Company, and was granted a lower annual interest rate of 5%.

But the South Sea Company broke the rules of the South Sea Act and began issuing stock before the government debt had been properly swapped for shares. Also, the government had failed to put a cap on the issue price of the new shares, which allowed the South Sea Company to issue £1,150 in stock for every £100 in debt. The difference was pocketed by the insiders.

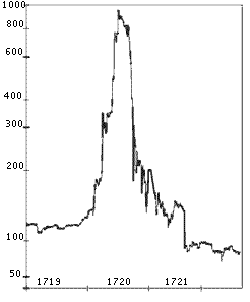

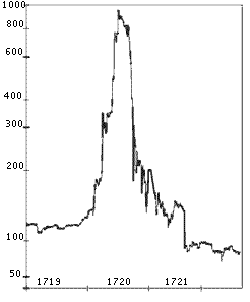

In July 1719, the South Sea Company went public. The company touted its shares heavily in newspapers and pamphlets. The public ate up the propaganda, which spoke of the “unlimited value of future trade with the Americas.”

As the South Sea Company’s stock price rose over £300, the stock showed signs of faltering. To prop up the price, the South Sea Company allowed investors to finance their stock purchases: 20% down, with payments every two months. This led to speculators buying five times more stock than they could afford. They gambled on the fact that if the price of South Sea Company’s stock continued to rise, they could simply sell their shares for a profit to someone else and not have to pay back what they owed using their own money.

As the stock surpassed £400, the South Sea Company took it a step further and used its own profits to loan investors up to £3,000 each to buy more of the company’s stock. Essentially the company was paying people to buy their stock. The stock broke over £600.

Copycats

The success of the South Sea Company’s public offering opened the floodgates to more companies and startups offering shares to the public. Many of them were ridiculous and outright fraudulent. One infamous prospectus stated that the company’s business was to carry on an “undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” But people were hungry to put their money to work. They had seen South Sea investors get rich, and they wanted the chance to invest in “the next South Sea”, much like people do today when they try to buy the next Apple, Facebook, or Netflix.

The South Sea Company did not take well to this. The scale of their scheme had gotten so big that it required all of the public’s money to remain afloat. So the government shut down other newly IPO’d companies for “unwarrantable practices.” But this had the opposite desired effect. People lost money in those stocks and sold off South Sea stock to compensate for their other losses. Eventually the South Sea Company began to show cracks.

The Crash

John Blunt and other South Sea Company insiders began to sell their shares. To provide themselves liquidity, they issued new stock at a whopping £1,000 per share with even more lax terms: only 10% down with no payments for an entire year. All the stock sold, and the South Sea Company sported a market valuation of £300 million. But when John Blunt offered a 30% dividend on the stock for the next ten years, it alerted investors to the reality that the South Sea was an unsustainable bubble. In fact, this is where the term “bubble” was first coined—during the South Sea Bubble in 1720.

Finally thinking rationally, speculators began selling their shares. This quickly devolved into a stampede of selling. The bubble burst, and the stock went into free fall.

The Aftermath

Five banks failed due to the bursting of the South Sea Bubble. There was rioting in the streets of London. Thousands of people, including many aristocrats, lost all their wealth. Some even committed suicide.

South Sea Company insiders such as John Blunt were put on trial, imprisoned, and their ill-gotten profits and estates were confiscated. Corrupt government officials were impeached. The funds were used to relieve victims of the investment fraud.

The South Sea Company appointed new directors, and its shares were divided between the Bank of England and the East India Company. The restructured South Sea Company continued to trade during peacetime until the end of The Seven Year’s War in 1763. It also continued to manage the government’s debt until the company was dissolved in 1853. When the government still hadn’t paid off the debt by World War I, the debt was restructured. As of today, nearly three centuries since the burst of the South Sea Bubble, the debt still hasn’t been paid off.